The MacCready Explosion

The MacCready Explosion

Each day as I read, write, and listen to podcasts and debates, I came across this idea on Ted Talks, The MacCready Explosion. It came up when researching a Green Party article, and it struck me as having considerable potential when assessing what is happening on our planet.

Many have heard the dire reports about species extinction and of the perma-frost being in serious decay, but have you thought about livestock and how that species affects global warming? The idea, of course, relates to the title of this post and is embedded in the following short introduction.

Culture as a Major Transition in Evolution

D.C. Dennett

Center for Cognitive Studies, Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts 02155

Excerpt:

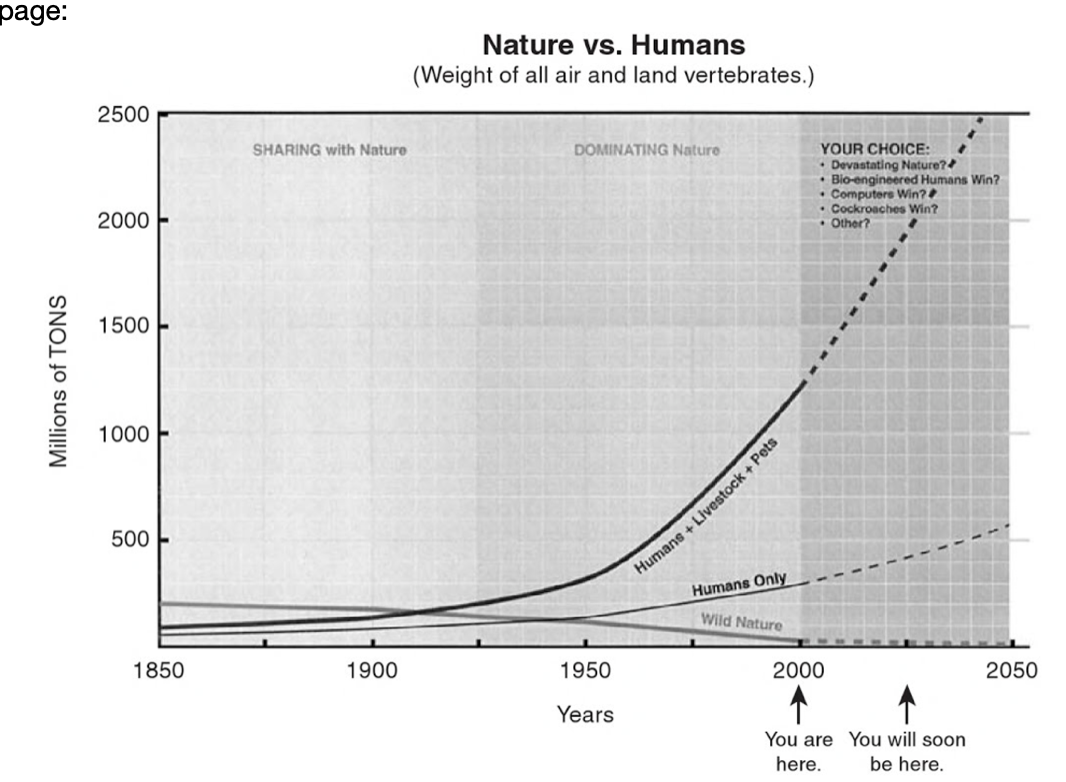

According to calculations by Paul MacCready (1999), at the dawn of human agriculture 10,000 years ago, the worldwide human population plus their livestock and pets was ~0.1% of the terrestrial vertebrate biomass. Today, he calculates, it is 98%! (Most of that is cattle.) His reflections on this amazing development are worth quoting:

Over billions of years, on a unique sphere, chance has painted a thin covering of life—complex, improbable, wonderful and fragile. Suddenly we humans . . . have grown in population, technology, and intelligence to a position of terrible power: we now wield the paintbrush. (MacCready 1999, p.19).

Some biologists are convinced that we are now living in the early days of a sixth great mass extinction event (the “Holocene”), to rival the Permian–Triassic extinction ~250 million years ago and the Cretacious–Tertiary extinction ~65 million years ago. And because, as MacCready puts it so vividly, we wield the paintbrush, this mass extinction, if it occurs, would go down in evolutionary history as the first to be triggered by the innovations in a single species.

Compared to the biologically “sudden” Cambrian explosion, which occurred over several million years ~530 million years ago, what we may call the MacCready explosion has occurred in ~10,000 years, or ~500 human generations (of course, thousands of prior generations were required to set up many of the conditions that made this possible).

There is really no doubt, then, that it has been the rapidly accumulating products of cultural evolution—technology and intelligence, as MacCready says that account for these unprecedented transformations of the biosphere. So Maynard Smith and Szathmary (1995) are right to put language and culture as the most recent of the “major transitions of evolution.”

This is a most astounding revelation that likely accounts for much of that which we now call “climate change” or “global warming”. We strongly suspect these changes are related to human activity, yet we don’t know to what extent we can mitigate the outcomes. To this point, we seem focussed on fossil fuels as a major culprit, yet I don’t know how much we have considered other sources.

That being stated, if climate change is largely caused by human activity, and I’m certain it is, I choose to believe we can at least try to do something to change the outcome. To not even try seems crazy.

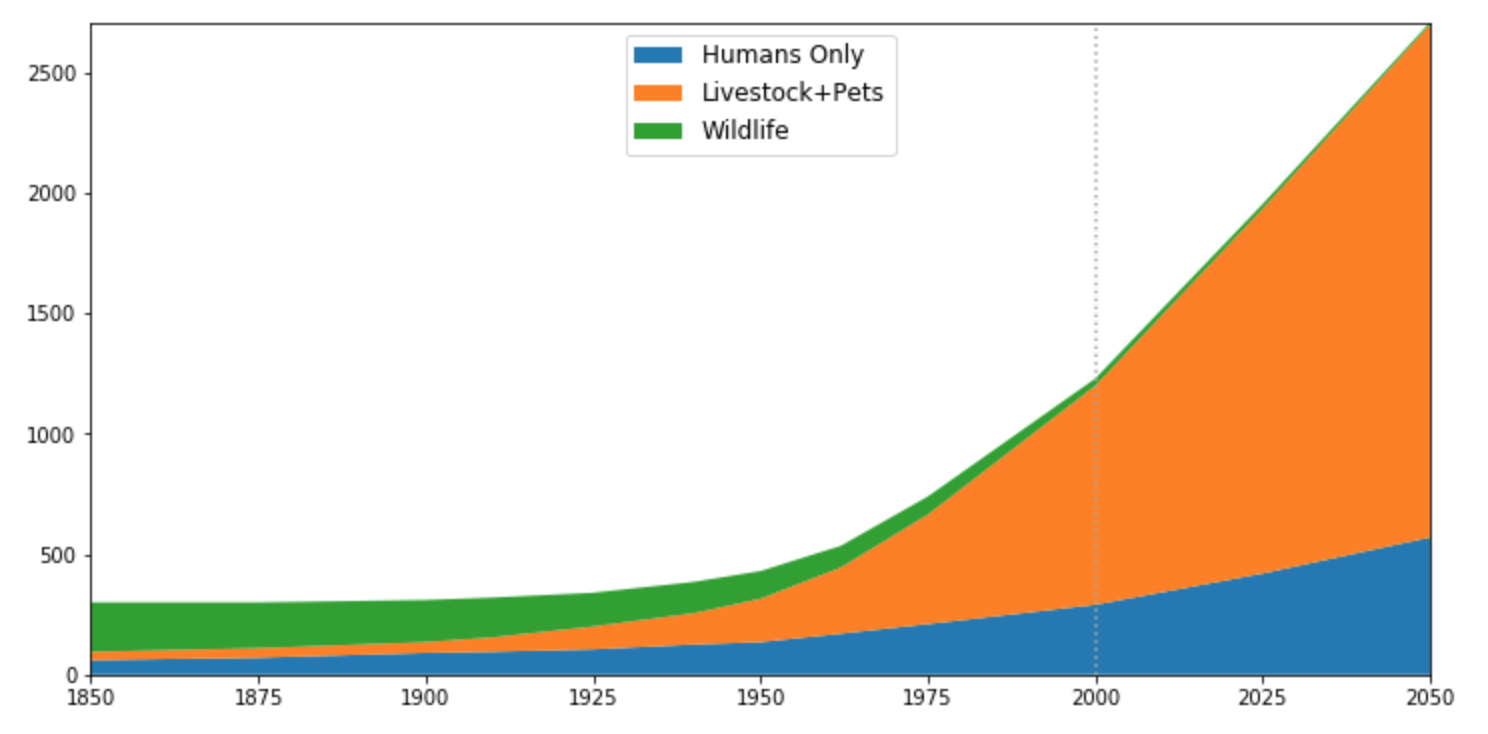

I think we can and it comes in the form of another paper, one by Nathan Daly, a software engineer, titled “Digging into the disappearance of nature’s land-living vertebrates.” It’s not a long read and you can skip the data contained with each of the several charts. You will see that simply reducing the number of livestock, and therefore our consumption of meat is likely to produce significant results. Given that livestock is a major contributor to greenhouse gas, that step provides a double win.

Comparing the introductory chart for his post with the one above, reveals the biggest single reduction can be made in the area of livestock. It’s somewhat harder to get rid of humans although we are well along the path of reducing our rate of growth.

Presented as ‘food’ for thought.

Cheers,

Harold

Note: I have not found any information that outlines how the author developed the data that support his conclusions so, at present, it is just another theory that seems worthwhile pursuing.

(2210)

Trackback from your site.