Fire Walkers: Chapter 1 – A Nuclear Challenge

Photo (1961): USAF Crash Rescue Crew From Cold Lake taken while in training at CFB Camp Borden

(Photo: Courtesy of Guy Venne)

Top Row: U/K, Ken Cuthbert, Les Eshelman, Al Edstrom, Ed Vallee, George Grimstead, Morris Hill,

Wally Armstrong, Fred Bamber, Roy MacDonald, U/K, Art Axani

Front Row: U/K, Instructor, Instructor, Harold McNeill, Instructor, Guy Venne, Instructor, U/K,

Denis Armstrong, Derek Bamber, U/K

(All names subject to clarification — Click photo to open, then click again for full-size download or printing. Names in bold, all Cold Lake High School buddies)

October 14, 2017 (4200)

Fire Walkers: A Nuclear Challenge

2011 will mark the 50th Anniversary of a unique experience in my life and that of several friends and neighbours from the Cold Lake area of Alberta. Forty-five men, ranging in age from twenty to thirty-eight, were selected to work as Civilian Crash Rescue Firefighters for the US Air Force at the Strategic Air Command base being built at the RCAF Station Cold Lake. For a full list of names of those selection Link here to Chapter 6,

Two other SAC bases built in Canada were also selecting civilians to perform the same duty – 45 for Namao (just outside Edmonton) and another 60 for Churchill in Manitoba. All were to be trained over the summer and fall of 1961 at the Crash Rescue Fire Fighter School in Camp Borden, Ontario, a school that had an established reputation as being the best in the business.

While a few of the men destined for Cold Lake had small town, volunteer firefighter experience, most, including myself, were taken in as raw recruits. Over a period of five months spread over two training groups, the men moved from the training stage to manning a full-service Fire Department. This included a process to select a Fire Chief and Crew Chiefs from within the ranks of those trained at Borden.

The expedited process resulted from the reluctance of the RCAF, in the politically charged climate of the deep Cold War, to have RCAF personnel fully integrated into what was essentially an independent USAF operation on Canadian soil.

For their part, the USAF was not able to field a sufficient number of firefighters to perform this duty due to a rapidly expanding Cold War Strike Force that stretched around the world. This included manning over 450 SAC bases within the continental United States, Alaska, and Hawaii.

Force that stretched around the world. This included manning over 450 SAC bases within the continental United States, Alaska, and Hawaii.

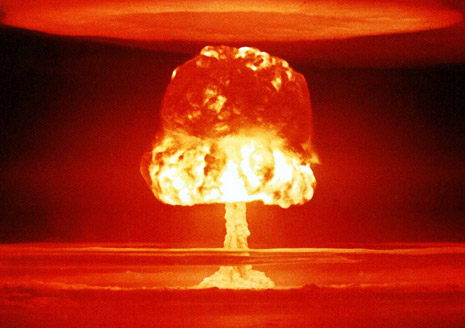

The threat of a nuclear attack and potential annihilation of mankind was one of the most feared events throughout the 1950s and 60s. The proliferation of nuclear weapons following the Second World Wars and the resultant partition of Europe lead to almost continuous conflict from 1914 through 1975 (the end of the Viet Nam War).

An all out Nuclear War between the Western Democracies and Russia would most certainly have ended life on earth as we know it. By way of comparison, the current day “war on terror” is a rather trivial event.

It was a time in our history when the Cold War mentality paralyzed much of the world and a time when Canada hosted a nuclear arsenal that was globally fifth in size behind only the United States, Russia, England, and France. The nuclear weapons in Canada, the subject of secret agreements, were stored across the country as well as carried aboard giant B52 bombers that circled high in the skies above the Canadian Arctic twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. The giant USAF Base at Goose Bay hosted between 12,000 and 15,000 USAF personnel in what was one of the largest USAF bases outside the United States.

(4782)

Fire Walkers – Camp Borden Fire School – Chapter 2 of 6

Fire Walkers – Fire School – Chapter 2

On July 25, 1961, our group of twenty-three was packed and ready for lift-off, the assigned transport an Air Force, Fairchild, C-119 Flying Boxcar, a supply and troop transport. For troops (and wannabe firemen), canvas slings hanging from the sides of the fuselage, provided a place to sit but little in the way of comfort. Immediately outside the fuselage the roar of the two 1500 hp radial engines made conversation nearly impossible.

With a painstakingly slow cruising speed of 200 mph, it was a long, bladder filled trip to Winnipeg where we stopped for a bathroom break, quick lunch and change of flight crew. By early afternoon we were off for the ten hour leg to Trenton. After a late dinner we bunked down but did not get much sleep that night as we all seemed to be giddy from the long flight and thinking about the new experience that awaited. Early the next morning we left by bus for the final 120 mile leg to Camp Borden.

As civilians we were assigned barracks separate from regular recruits – I suppose the brass didn’t want our rag-tag group of civilians to unduly contaminate their sparkling fresh troops. The accommodation and food was great but we generally stood out like sore thumbs in the mess hall and around the base where all military personnel sported freshly pressed uniforms and spit polished boots. By the sarcastic comments directed our way, it was clear the regulars didn’t view us with high esteem.

From the course overview given over the first few days, it was certain the next several weeks would be hard work, both in class and in the field, as first we studied, then put into practice, the skills required to become top-notch crash rescue fire fighters. The real shocker came on our first visit to the practice area with Corporal Breckinridge, our field trainer.

(2008)

Fire Walkers: – Forming a Fire Department, Chapter 3 of 6

Fire Walkers – Forming a Fire Department, Chapter 3

On returning to Cold Lake in early October, 1961, it was, as the saying goes, ‘jumping from the frying pan into the fire’. Fresh from basic training, we were now tasked with actually learning the day to day aspects of crash rescue work in real time. The USAF personnel having been temporarily seconded to fire duties at the SAC Site had a full training program set and ready to go when we arrived.

Fire Truck Familiarization

First off the mark was learning to use the USAF equipment, none of which was available at Camp Borden. The three main pieces were two giant O11-A foam trucks and a smaller R2 (we call the R-Deuce) rescue truck. There was also one tanker truck (for hauling water/extra foam cans) and several pieces of smaller equipment used on the tarmac for fire protection around the  aircraft during engine starts.

aircraft during engine starts.

Photo: Crew from 0-11-A and others tackle fire at a mock crash site. One man remains in the turret while others approach the mock aircraft with handlines. Location of this practice area is unknown.

Normal crew size on a 011-A was four – the driver and right hand crewman operated the two electronically controlled roof turrets, while two others operated the lines. The hand line operators could also open a roof hatch and operate the turrets by hand (as in above photo). In approaching a scene, the two hand line men manually operated the turrets while the truck approached and after it had stopped the driver and front fireman would take over with the trigger grips while the hand line operators left the cab to continue to knock down the flames.

It was spectacular watching a well coordinated attack knock down a wall of flames with those twin turrets that could lay down tens of thousands of gallons of foam (a mixture of animal rendering and water) within a matter of seconds. There was little that could match the adrenalin rush felt when approaching that wall of fire.

In a real life situation, if the aircraft was fully engulfed in flame it was understood the chance of pilot or crew survival would be limited but if there was even the slightest chance of survival, our challenge was to affect a rescue. While we trained for specific positions, all members of our crew were capable of filling every position as needed.

(2447)

Fire Walkers – Daily Routines – Chapter 4 of 6

Fire Walkers – Daily Routines – Chapter 4

Every man dropped what they were doing and ran to their assigned position as the klaxon horn souded in the station. Our trucks were already rolling as dispatch radioed the call that a CF-104, had crashed off the end of run-way 130 a short distance south of the base. It was believed the pilot had ejected but nothing further was known and as our crews were  closer, we were instructed to continue to scene.

closer, we were instructed to continue to scene.

Using local maps of the myriad of small roads south of the airport, we left the station with further directions to be passed along from the helicopter rescue crew dispatched to the scene.

During our time at Cold Lake, the most common call for assistance to the RCAF resulted from a CF-104 in difficulty. While the aircraft was popular with Canadian pilots it was challenging to fly and air forces around the world experienced losses of up to 45% which is higher than any aircraft outside of war time. That being said, operations with the RCAF would see the CF-104 put in more air time per craft than any other nation and Cold Lake was at the training epicentre.

(2938)

Fire Walkers – Disaster Strikes – Chapter 5 of 6

Fire Walkers – Disaster Strikes – Chapter 5

Flying at 5000 feet, fifty miles northwest of Cold Lake it was now evident the cloud of heavy black smoke that was building to several thousand feet was coming from the base. As per normal procedure I made radio contact with the tower, advised of my location and intention to pass by the north side of the base control zone and also requested they close my flight plan. Having received confirmation I then advised I was a fireman at the SAC Base and inquired as to the source of the smoke. The tower advised there had been a major explosion at the SAC Site and all available firemen were being called to duty. The tower advised the base was closed to all air traffic until further notice.

As I passed by the control zone about 14 miles north, it was evident the pall of smoke was rising from the large composite building that housed most of the infrastructure at the SAC base. This included our Fire Department complex in the north-west corner.

After landing and securing the airplane at the main dock in Cold Lake, I jumped in my car and headed to the base. On arrival I reported in to a temporary HQ in a hanger about 200 yards south of the Fire Hall and learned that all but about five of the off-duty men had already reported for duty. In a short brief by one of the George Grimstead, one of the Crew Chiefs, I learned a major explosion had occurred in a repair area in the southeast corner of the building. The cause was, as yet, unknown.

(715)

Fire Walkers: Appendix Chapter 6 of 6

Fire Walkers: Appendix Chapter 6 of 6

Personnel Lists for Cold Lake, Namao and Churchill

If you happen to read this story and know someone who worked for the Fire Walkers in the early sixties, I would like to add that person to one of the following lists. My contact numbers are listed below or you may simply post a note at the end of this Chapter.

Photo: Shoulder patch that was designed by one of the Fire Crew and worn on our civilian jackets. The fist with lightening bolts was taken from the Strategic Air Command Crest.

Over time I would like to include as many names as possible and post a short biography about each person, written either by the person named, by a friend or another Fire Walker or by someone from that persons extended family. A list of names is provided below.

A picture of the training crew or of time spent at one of the three bases or future postings would also provide excellent background.

Regards

Harold McNeill

Victoria, BC

Phone: 250-479-7532

Email: lowerislandsoccer@shaw.ca

Email2: harold@mcneillifestories.com

Face Book: Harold McNeill or by the above email

Blog: www.mcneillifestories.com

(909)