Author Archive

Laura Isabel: Uffda! – A New Beginning – Chapter 4 of 5

Laura Isabel: Uffda! – A New Beginning – Chapter 4 of 5

Never one to look back with yearning or regret, Laura married a neighboring farmer, Wilfred Skarsen , and the happy couple started a whole new life with Dianne, who was just approaching her teens. Uncle Lennel (Wilfred’s older brother) lived with them while sharing the original family home until, 1982, at the age of 73, Lennel married Emma Adele Shular. Both  men, who, to that point, remained bachelors, were suddenly the step-fathers to 13 children and countless grandchildren. Both stepped into those big shoes as if they had been groomed for the roles their entire lives.

men, who, to that point, remained bachelors, were suddenly the step-fathers to 13 children and countless grandchildren. Both stepped into those big shoes as if they had been groomed for the roles their entire lives.

Laura’s beau, Wilfred, was the sixth of seven sons of Oscar (1880) and Petra (1890) Skarsen (Myhre) whose families began homesteading the Riverhurst area in I939. This enterprising Norwegian-Canadian family – son’s, Lennel, Julian, Melvin, Morgan, Percy, Wilfred, Wilbert and, daughter Stella – quickly expanded their interests into mixed farming, fishing, hunting, logging and milling, trapping, carpentry and commercial painting. They were an industrious family group and added much to life in the Cold Lake area.

Laura and Wilfred continued to live on the original Skarsen homestead in Cold Lake, however when Highway 55 was widened in 1981, they moved the entire farm, lock stock, barrel and grainery, 500 yards to the north-west. This new location, with freshly painted granaries, a new barn and a backdrop of pine and poplar, quickly became a showcase as Laura and Wilfred expanded the gardens and expansive lawns.

Their efforts lead to an Alberta Government “Farm Beautification Award” in 1985, just three years after moving to the new location. Laura also received personal recognition in 1996 when she was awarded the Provincial “Imogene Duce Award” for her activity with the local TOPS Chapter. A few words from that award express the sentiment of any who have come to know Laura:

“Love, caring and understanding – a person possessing an abundance of any one of

these qualities is truly exceptional. We have just such an exceptional lady in our chapter

and she is perhaps even more exclusive because she excels, not just in one but in all three

of these categories…” (Diana French, Chapter Leader, TOPS AB4003, Riverhurst)

(973)

Laura Isabel: The Young Woman – Chapter 3 of 5

Laura Isabel: The Young Woman – Chapter 3 of 5

During her teen years, Laura and her family went about the daily routine of cooking meals, working in the garden, mowing hay, looking after the animals, cutting wood and all the chores that were part of early farm life on the prairies. Because they were so close to Birch Lake, the kids had many fond memories of swimming and boating on those hot summer days when they could sneak away from their daily chores.

Always a homebody, Laura traveled for the first time, at age 16, to work on a family farm outside Battleford looking after five kids under the age of four. She became so homesick after a couple of weeks that her dad traveled to Battleford in his Model T to pick her up. Her next job was working as a cook for a road construction crew as they rebuilt Highway 55 (now Hwy 3) out of Glaslyn.

Always a homebody, Laura traveled for the first time, at age 16, to work on a family farm outside Battleford looking after five kids under the age of four. She became so homesick after a couple of weeks that her dad traveled to Battleford in his Model T to pick her up. Her next job was working as a cook for a road construction crew as they rebuilt Highway 55 (now Hwy 3) out of Glaslyn.

When Laura was 21, the family suffered a double tragedy when her brother, Leonard, then twenty-five, was drowned in the Shuswap River while trying to save a friend’s life after the friend had fallen from a log boom on which they were working. While the whole family grieved over the loss, their father Bill took the death particularly hard. Later that winter he contracted scarlet fever and, tragically, in the early spring of 1940, he died at the age of 51 just a few months before Laura married Dave McNeill.

Following the death of her son and husband, life for her mother and the family became very difficult. Shirley was barely two, Helen and Marcia were five and seven and Tonnie had just turned ten. Melvin returned home to help his mom, followed later by Clifford who had served in the military until the end of the Second World War. In order to help make ends meet, Lilly, Helen and Marcia worked on neighbouring farm but the nearly all the money they earned was deducted for room and board and any remaining, which was pitifully little, was deducted from her meager widow’s pension of $30 per month.

(859)

Laura Isabel: The Early Years – Chapter 2 of 5

Laura Isabel: The Early Years – Chapter 2 of 5

Laura was the third of ten children born to Bill (William Skyler -1888) and Lillie Cressie Wheeler (Elliott – 1896). Siblings included Leonard (1914), Evelyn (1916), Kenneth (1920), Melvin (1922), Clifford (1924), Tonnie (1928), Marcia (1932), Helen (I934) and baby Shirley (1938).

In the early spring of 1924, Bill and Lilly, along with other family members, pulled up stakes and headed out from the Alsask, Saskatchewan, to take up homesteading at Birch Lake, a few miles North-East of Glaslyn. At that time the five children ranged in age from 2 to 10  years and Lilly was expecting her fifth. Clifford was born that September. Lilly attributed the distinctive brown birth mark prominently displayed on Clifford’s forehead to the fright she suffered when Melvin, then two, almost fell from the caboose while crossing a river enroute to Birch Lake.

years and Lilly was expecting her fifth. Clifford was born that September. Lilly attributed the distinctive brown birth mark prominently displayed on Clifford’s forehead to the fright she suffered when Melvin, then two, almost fell from the caboose while crossing a river enroute to Birch Lake.

Photo: The wagon train ready to head out. Howard (Laura’s dad’s brother) and Myrtle Wheeler, her mom and dad, Lilly and William, grandparents, and siblings, Kenneth and Evelyn.

While Bill and Lillie were able to provide their family with a comfortable life (by the standards of a 1920’s homesteader) it did require the labour of all family members. That first summer, after the crops and garden were planted (some of the land was previously broken), Bill set about building a three room log house with sod roof, mud plastered cracks and whitewashed exterior.

(1468)

Laura Isabel: Prologue – Chapter 1 of 5

In Memory of

Laura Isabel Skarsen (McNeill) (Wheeler)

A True Canadian Pioneer

1918 – 2008

Link to Part 1 A New Beginning

Link to part 2 The Early Years

Link to Part 3 The Young Woman

Link to Part 4 A New Beginning

Link to Part 5 The Final Chapter

Laura Isabel: Prologue – Chapter 1 of 5

It is amazing how much the world changed during Laura’s lifetime. Born in a Southern Alberta dust storm, at five years old she was on a wagon train with her parents and grandparents as they headed to Northern Saskatchewan in order to create a new life on a homestead.

She grew into adulthood in the Great Depression as clouds of dust blanketed the prairies and jobless men road freight trains in search of work. The ‘great’ depression barely ended when the Second World War seized the world in it’s powerful grip. It was a character building period that began in the ashes of one world war and ended with the euphoria that accompanied the years following World War II.

(2065)

Harlan: Our Dad is Missing – Chapter 6 of 6

Photo (family files): Dad is Missing. The last we saw of our Dad was when he came to the door of the bar and waved to us: “I’ll be right there, I’m just having a quick chat with some guy’s I met.”

Link to Next Post: Edmonton

Link to Last Post: Movie

Link to Family Stories Index

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

July, 1949

The bus driver, having pulled to the side of the highway after being approached by one of the passengers, walked down the isle to the seat Louise and I occupied. “What’s wrong kids?” he asked in a gentle, caring voice. Louise and I were huddled in our seats as tears trickled down our cheeks. Louise, on the outside, responded in a quiet, quivering voice, “You, you left my daddy behind!” She continued to cry as we held each other.

(1617)

Harlan: Movie Night – Chapter 5 of 6

Photo (FB Source). Once every couple of weeks, a man came by with his movie projector, a projector something like the one used in this photo.

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

Spring, 1949

When the Movie Man came to the Harlan Community Hall not far from our farm, it was a highlife for the whole community. He would set up his gas powered generator outside the hall to run the projector and we would settle in for an evening of entertainment. At 7:00 pm they would cover the windows with blankets, close the doors and the movie would flicker to life on the portable silver screen.

Link to Next Post: Our Dad is Missing

Link to Last Post: Hunting Crows

Link to Family Stories Index

(1965)

Harlan: Snakes and Horses – Chapter 3 of 6

Photo (Web) This red sided garter snake along with hundreds of other species can be found by the thousands across the prairies. The snakes are great for scaring people.

Link to Next Post: Hunting Crows

Link to Last Post: Interesting History

Link to Family Stories Index

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

Early Summer, 1949

One thing that is etched in my memory from our months in Harlan was the millions (perhaps trillions) of ‘garter snakes’ that thrived in the grass and bush land throughout the area. Most of these little snakes measured between 8” and 18” in length and although not poisonous, they could sit back, hiss and flit with the best of their forked tongue relatives.

While many people have a built in aversion to snakes (probably stemming from that incident in Garden of Eden), Stan and I had no such qualms. We took great pleasure in chasing down those slithering, twisting, hissing and flitting reptiles, grabbing them by the tail and putting them in a pail or box for ‘later’ use. That use usually involved chasing the girls at home and school.

(1850)

Harlan: A Tragic History – Chapter 2 of 6

Photo (Frog Lake Memorial): One man who died was the John Delany, the Grandfather of my Aunt Hazel (wife of my mom’s brother Melvin Wheeler), all part of the interesting history of our family. Note, many of these historic signs still denote the event as a Massacre in the midst of the Northwest Rebellion. Little mention is made at these historic sites of the attempt by an “Indian Agent” follow the “letter” of the laws passed in Ottawa, to starve the local bands into full submission to his wishes.

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

Early Spring, 1949

While our home in Marie Lake, Alberta (20 miles north of Cold Lake), was nestled within the pristine beauty of the lakes and evergreen forests dotting Northwestern Alberta, Harlan District was spread out along fields and poplar forests that gently rose from the banks of the North Saskatchewan River. Situated just inside the Saskatchewan border with Alberta, the community was less than ninety miles south-southeast of Cold Lake. Today, it remains a small farming community. Most things remained the same when my sister, Louise, and I lived there for a few months over the spring and summer of 1949. Louise was six and I was nine when we moved in with Aunt Liz (Dewan-McNeill) and Uncle Warren Harwood lived on a farm property in an area that was home to many in the

extended Harwood Family.

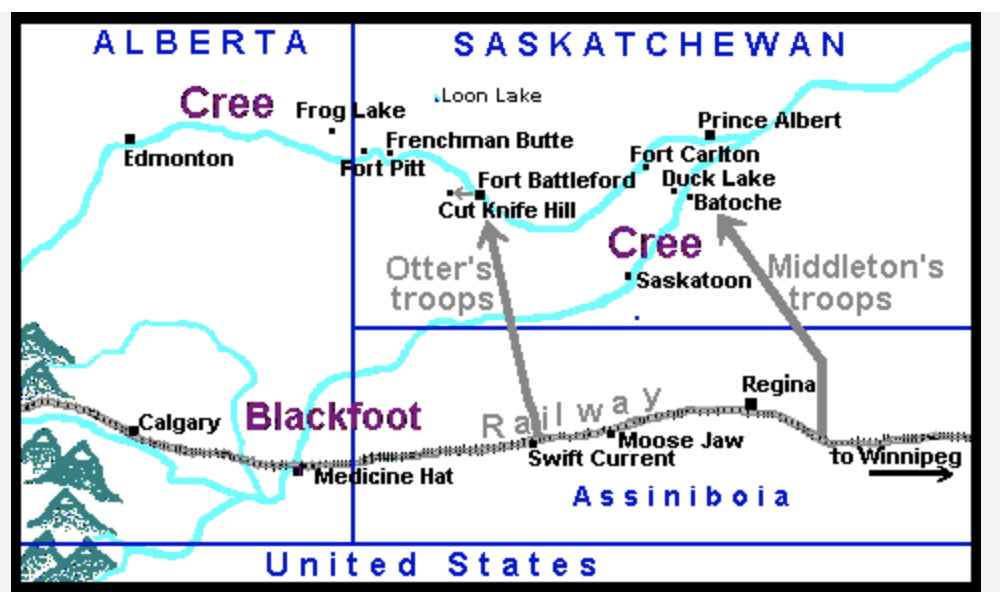

During that spring and summer, our cousins Betty (10) and Stanley (7), explored the grassy fields and poplar woodlands around the farm. Of course, we were oblivious to a significant piece of Canadian History that played out just over sixty years earlier – The “Frog Lake Massacre of 1887”.

During that spring and summer, our cousins Betty (10) and Stanley (7), explored the grassy fields and poplar woodlands around the farm. Of course, we were oblivious to a significant piece of Canadian History that played out just over sixty years earlier – The “Frog Lake Massacre of 1887”.

Calling it a massacre was wrong, as the more appropriate name should have been “Attempted Genocide at Frog Lake” or “The Frog Lake Uprising“. While some changes slowly seeped into the historic narrative, much in the way of naming is yet to be addressed by the Federal and Provincial Governments in the naming of sights and events.

That ill-fated attempt at genocide might have succeeded if bands had not risen against the deliberate starvation through federal government policies designed to subjugate the original inhabitants of that area. While the Indian Agent in Frog Lake bore a substantial part of the blame, Sir John A. MacDonald and his government were the architects of a policy that decimated many local Indian bands across Canada. Some tried to justify what happened as part and parcel of the challenges of “taming this new land”, but that explanation falls far short in explaining the brutality of the government policy and particularly the actions taken by many “Indian Agents.” assigned the task of handing out food supplies.

At the time the four of us were playing in the fields, we now know a member of our own family, Aunt Hazel Wheeler (nee Martineau), the wife of Mom’s brother, Melvin Wheeler, traced her family history directly to those tragic events that played in the Harlan District over the fall of 1887.

The farm where we lived with Uncle Warren and Aunt Liz Harwood (nee McNeill) was twenty-five miles southeast of Frog Lake, thirteen miles from Onion Lake and five miles west of Fort Pitt. The district became the epicentre of a rebellion of which the charismatic Métis leader, Louis Riel, was the prime mover, who chaffed at the injustices heaped upon the Cree and other tribes by the Federal Government. Riel was able to weld the diverse Indian Nations together in common purpose.

In his book, The Frog Lake “Massacre”, Bill Gallaher writes: “Superintendent Crozier and a contingent of policemen aided by a small volunteer force from Prince Albert, had confronted Louis Riel and his rebels, some of them Cree, at a place called Duck Lake, a few miles east of Fort Carlton. After the ensuing battle, 14 men lay dead.” (p. 102).

News of the confrontation quickly spread to the tribes in the Frog and Onion Lake area, where activist leaders, including Wandering Spirit, Man Who Speaks Another Tongue, and others who, gained a substantial following. Much of their anger was focused on one man, Thomas Quinn,

the Ottawa-appointed Indian Agent at Frog Lake. The man was an arrogant, stingy Scotsman responsible for enforcing Federal Government policy regarding the distribution of food supplies. The bands were in desperate straits after being forced out of their traditional hunting grounds and left utterly dependent upon government handouts.

Quinn took his directions to heart by forcing the largely peaceful Indian bands to bow to his every whim before he would release any food and other supplies agreed upon in the treaties. As the tribes became increasingly desperate and as their land base continued to shrink under the onslaught of the white settlers, it was not long before their traditional food supplies all but disappeared. Pleas for relief emanating from moderate leaders, including Chief Big Bear, fell upon deaf ears at Fort Battleford and Ottawa.

Having heard of Louis Riel’s initial successes in confronting government forces, activist leaders convinced many warriors to stand and fight rather than bow to the dictatorial Indian Agent. To resolve the situation, a meeting with the local settlers and Indian Agent would occur at Frog Lake:

“The air in the room was hot and close, thick with pipe smoke and body odour. All of the whites in Frog Lake had gathered in John and Theresa Delaney’s house to discuss Dicken’s message (a message from Inspector Dickens of the North West Mounted Police suggesting all the white settlers at Frog Lake, evacuate the community immediately and head to Fort Pitt), viewed by some as an emergency. It was near midnight as Theresa served tea and coffee strong enough to make sleep a far off in the country.” (Gallaher, p. 103)

“I noticed, as I’m sure others did, that he didn’t mention the Indian’s dislike of Quinn – they always called him “Dog Agent” or “The Bully” behind his back – and that perhaps he should go too.” (Gallaher, p. 105)

“Early the following morning, the group was taken hostage by the rebels, then under the leadership of Wandering Spirit. While being forced back to the Cree village, Quinn suddenly stopped and refused to follow instructions. Wandering Spirit stepped in front of the belligerent man, “You have a hard head, and I wonder if there is anything in it? He raised his rifle and shot Quinn through a head not so hard that a bullet couldn’t split it open…” (Gallaher, p. 106)

The sudden, violent killing of the “Dog Agent”, Quinn, left the remaining hostages scrambling for their lives:

“My mind was churning madly. We hadn’t taken more than a few steps when John Delany cried, “I’m shot!” He reeled several feet away like a drunkard, then staggered back and collapsed at Theresa’s feet. Oh, my God! Theresa cried. “Father, Father!” As she called, one of the priests, Father Fafard, came running to her side and dropped to his knees. Delany lived only long enough to hear the priest administer consolation and say, “You are safe with God, my brother.” These words had just passed Fafard’s lips when Man Who Speaks Another Tongue shot him in the face. He fell across Delany’s corpse.” (p. 128)

The uprising had passed the point of no return as the rebellious leaders and their followers headed toward Fort Pitt to confront the government forces. Only a few days passed before miserable weather a lack of weapons, food, and other supplies led to the collapse of the resistance, but not before many more had died in skirmishes in the valleys and hills surrounding Harlan, Fort Pitt and Frenchmans Bute.

The eight Indians, considered ring leaders, were arrested, and taken to Fort Battleford for trial, the outcome of which was never in doubt. After being convicted, they were hanged on makeshift gallows within the Fort. Chief Big Bear, the moderate leader of the Cree, who was present for the hangings, was then put on trial believing that he, as the leader, was ultimately responsible for the rebellion. After being convicted, he spoke eloquently in defence of his people:

Photo (Web File): The eight Rebellious leaders were hanged in a public event at Fort Battleford barrack square on November 27, 1885. Their bodies were unceremoniously interred in a scrubby bush area below the Fort. More photos and words follow near the end of this story. The men hanged—Kah-Paypamahchukways, Pahpah-Me-Kee-Sick, Manchoose, Kit-Ahwah-Ke-Ni, Nahpase, A-Pis-Chas-Koos, Itka, and Waywahnitch.

Following the hanging, Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) was put on trial a sad end to a popular leader. In 1871 he was the leading chief of the Prairie People and by 1874, headed a camp of 65 lodges (approximately 520 people). His influence rose steadily in the following years, reaching its height in the late 1870s and early 1980s. Due to events leading to the Frog Lake Uprising, his power was slowly eroded by the more aggressive leaders for reasons outlined later in this story. Following is the full Chief Big Bears full speech to the court as translated from the original Cree.

I think I should have something to say about the occurrences which brought me here in chains! I knew little of the killing at Frog Lake beyond hearing shots fired. When any wrong was brewing, I did my best to stop it in the beginning. The turbulent ones of the band got beyond my control and shed the blood of those I would have protected. I was away from Frog Lake a part of the winter, hunting and fishing, and the rebellion had commenced before I got back. When white men were few in the country, I gave them the hand of brotherhood. I am sorry so few are here who can witness for my friendly acts.

Can anyone stand out and say that I ordered the death of a priest or an agent? You think I encouraged my people to take part in the trouble. I did not. I advised them against it. I felt sorry when they killed those men at Frog Lake, but the truth is when news of the fight at Duck Lake reached us, my band ignored my authority and despised me because I did not side with the half-breeds. I did not so much as take a white man’s horse. I always believed that by being a friend of the white man, I and my people would be helped those of them who had wealth. I always thought it paid to do all the good I could. Now my heart is on the ground.

I look around me in this room and see it crowded with handsome faces—faces far handsomer than my own. I have ruled my country for a long time. Now I am in chains (Photo Left on right arm) and will be sent to prison, but I have no doubt the handsome faces I admire about me will be competent to govern the land. At present, I am as dead to my people. Many of my band are hiding in the woods, paralyzed with terror. Cannot this court send them a pardon? My own children—perhaps they are starting and outcast, too, afraid to appear in the big light of the day. If the government does not come to them with help before the winter sets in, my band will surely perish.

But I have too much confidence in the Great Grandmother to fear that starvation will be allowed to overtake my people. The time will come when the Indians of the North-West will be of much service to the Great Grandmother. I plead again to you, the chiefs of the white man’s laws, for pity and help to the outcasts of my band!

I have only a few words more to say. Sometimes in the past, I have spoken stiffly to the Indian agents, but when I did so, it was only to obtain my rights. The North-West belonged to me, but I perhaps will not live to see it again. I ask the court to publish my speech and to scatter it among the white people. It is my defence.

I am old and ugly, but I have tried to do good. Pity the children of my tribe! Pity the old and the helpless of my people! I speak with a single tongue, and because Big Bear has always been the friend of the white man, send out and pardon and give them help! How! Aquisanee—I have spoken!

Big Bear was sentenced to three years of hard labour to be served at the Stoney Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. He was taken away in shackles and leg irons and put on a train heading to Stoney Mountain – a proud leader to the end. He died 1888.

Eighty years later, the following passage, written by our Aunt Hazel Wheeler (Martiniau) about her parents and Grandparents, appears in “The Treasured Scales of the Kinosoo“, a book of life stories of those who settled the Cold Lake area:

“Father (referring to her father) was transferred to Onion Lake in 1901 as a Hudson’s Bay Company Agent. He met and married Margaret Delaney. Margaret was the daughter of a native mother and an Irish father. Her father (Aunt Hazel’s Grandfather), John Delany, was killed in the Frog Lake Massacre, and she was raised by nuns at Onion Lake. Father was part French and part Scottish, and he used to tell us that we were a little bit of everything and not much of anything.” (p. 4)

Aunt Hazel was one of thirteen children in the Martineau family. It was a grand family that included five adopted children saved from the orphanage after the death of their parents. It is little wonder that Aunt Hazel’s mother was known as ‘Grandma Martineau’ to everyone in the Cold Lake area. She was well into her eighties when she passed away (reference picture of Grandma Martineau sitting on the logs at the Martineau Camp in Chapter 3 of that series).

Photo (Family Files). Aunt Hazel and Uncle Melvin Wheeler are sitting with their two sons, Timmy, and Randy, at their home in Cold Lake.

The following quotes from Aunt Hazel are added as they relate to other events and people in those early years of our family travels throughout the Northwest.

“Johnny Cardinal operated the ferry on the North Saskatchewan River near Frog Lake at the time of the Massacre.” (p. 5). (The Cardinals were another well-known Cold Lake family).

“A group of surveyors worked north of Cold Lake before 1910, setting their base camp at an unnamed river that flowed into Cold Lake. They depended upon Adrian (Adrian Martineau, one of Aunt Hazel’s brothers) for their food supplies. On one occasion, the supply wagon bogged down due to heavy rains at Onion Lake. When the needed supplies finally arrived, the head surveyor announced that he named the river at their base camp Martineau to remind Adrian of when he and his men (the surveyors) almost starved.” (p. 5)

Adrian passed away in 1944, the year we moved to Cold Lake and lived on the banks of the Martineau River, very near the area where the surveyors almost starved in 1910. In the summer of 2010, our oldest son, Jay McNeill, and I visited many historic sites stretching from Frog Lake and Onion Lake to Fort Pitt and Fort Battleford. Our visit included a stop at the grave sites of the eight settlers killed and buried at Frog Lake and the eight Indian leaders hanged and then buried on a sidehill below Fort Battleford.

Given that Fort Battleford is a National Historic site, it is a national disgrace that the hanged men, leaders of the day who attempted to help their people, have been relegated to weed-infested, rocky sidehill several hundred feet below the Fort. They were heroes, and their History is cast aside in favour of a different narrative of those times.

below the Fort. They were heroes, and their History is cast aside in favour of a different narrative of those times.

The graves below Fort Battleford are located no more than a few hundred yards from the spot where first our Grandparents McNeill and several of their children, including our Dad (two years old at the time), camped in 1910 as they were making their way by wagon train from South Dakota to Alberta to build a new life on the shores of Birch Lake. Birch Lake is some seventy miles north of Fort Battleford near Glaslyn, where Chapter 1 of this story began.

One year later, in 1911, our future Great-Grandparents and Grandparents Wheeler and some of their children, immigrated from Michigan to Sibbald, Alberta. In 1924, due to serious drought conditionst, some of those same families (some now married and with children of their own), left Sibbald, Alberta. for Birch Lake, Saskatchewan. Included in that group was a child who would later become our mother, Laura Skarsen-McNeill (Wheeler). During that wagon-train trip, they made a five-day layover below Fort Battleford, before leaving for Birch Lake, where they would stake a land claim on quarter section of land very near the McNeill family.

The full story of both families travels from the United States to Canada in 1910, is now being written and will become the first half of a family book that follows our families for a hundred years from the 1860s – 1960s

Harold McNeill

July 2010

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

Link here to photo’s of Frog Lake adventure: LINK HERE

September 19, 2012. The following information was plucked from a Genealogy site:

Also, a note by Phylis Wicker Glicker

Hazel Martineau [Wheeler] daughter of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau b. Oct. 18, 1875, St. Boniface, Manitoba, Canada, and Margaret Delaney b. Nov. 30, 1885, Frog Lake, Alberta, Canada. Adrien is the son of Herman Martineau b. Brittany France mar. (1) Annie Macbeth (2) Angeline LaBelle. Herman Martineau is the son of Ovit Martineau b. Brittany, France. I have just begun researching the Delaneys and Martineau”s so I don’t have much. But I would love to hear from you and share what I have. I was married once to Frank Martineau, grandson of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau and would love to learn about Margaret Delaney’s family for mine and my children’s sake.

Email: pwicker@telus.net

Harold Comment: I am not sure if this is correct, but it seems to fit with the details I have previously researched.

(4034)