Chapter 4: Fish Attack – A Military Aircraft Down in French Bay

Photo (From the files of a High School friend and former workmate, Guy Venne). The RCAF often moored their DHC-3 Otters at the main dock in Cold Lake and the above aircraft appears to be the same one that is the subject of this post. Guy had taken several photos of the crash scene in French Bay, but all those photos were seized by the Air Force as part of their investigation.

The three photos displayed in this story were also taken taken by Guy, one before the crash (above) and two after the craft had been towed to the main dock at Cold Lake. Damage to floats suggested a collision, but the Air Force had other ideas. The whole story was to become cloaked in secrecy (photos in footer).

October 10, 2014. As a result of new information coming into my possession along with never before released photographs of the airplane involved, the story and series is being updated and will be completed sometime late next week. Thank you for your patience. It seems likely the conspiracy of silence that existed then, continues to this day. Harold

Link to Next Post: Sampi gets hooked

Link to Last Post: The Rush is on.

Link Back to Adventures Index

1. In Training

The young air force pilot from the RCAF Station at Cold Lake was completing the final hour of his checkout on the float equipped DHC-3 Otter, one of the many dozens of Otters purchased from the deHavilland Corporation for use at Air Force bases across Canada. These aircraft, mostly float equipped, were stationed further north purportedly as a means to service remote northern outposts and the mid-Canada and Arctic Distant Early Warning (DEW) stations.

On this day, as the pilot set up for his third ‘glassy water’ landing in French Bay, he was making his final approach. As his plane continued towards the water, he guessed his height against the shoreline about a quarter mile off his port wing. His altimeter indicted a height of about 200 feet (1884 ASL) according to the last barometric reading entered.

While the altimeter provided a good estimate of altitude, the reading was only as good as this last barometric reading. Things could change quickly if a high or low pressure system was moving through, so actual height could easily vary by fifty feet or more. At low altitudes, over glassy water, this held the potential for disaster.

While the altimeter provided a good estimate of altitude, the reading was only as good as this last barometric reading. Things could change quickly if a high or low pressure system was moving through, so actual height could easily vary by fifty feet or more. At low altitudes, over glassy water, this held the potential for disaster.

Many experienced bush pilots lost their lives when they failed to properly set their landing approach attitude for glassy conditions. For inexperienced pilots, the chance of having a nasty accident was even greater.

Photo (Web Source): Even the most experienced pilot who wasn’t paying close attention, could end up making a mistake when approaching the surface of a lake that looked like this.

While this pilot had more than two hundred hours on the Otter, this was only his fourth hour of float work and his third glassy water landing. Granted he had an experienced pilot sitting by his right hand, but when things went wrong on landing, the danger could escalate exponentially in a split second.

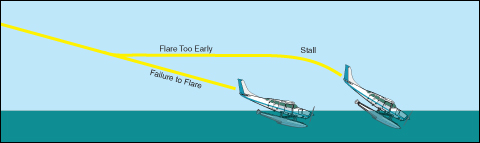

In making a glassy water landing it was essential to carry out an approach that allowed the aircraft to slowly sink onto the surface rather than picking the exact moment to flare out and settle on the surface. When deep shadows that come with the late evening (photo above) or early morning, special caution was needed at any height below 200 feet. The further from shore the landing, the higher the final landing approach needed to begin.

During the war when pilots were making glassy water landings out of site of land, they would often throw articles out of the aircraft in order to get some idea of the distance to the surface. When out of sight of land, it could be easy to make an error of a thousand feet or more.

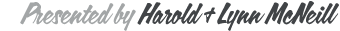

Two diagram in the footer show the proper landing procedures for glassy water as well as the inherent danger of selecting the wrong approach. An inadvertent moment on one of these landings nearly cost me my life while hauling fish near LacLaBiche. The incident happened around the same year the RCAF pilot was completing his float endorsement on the Otter (c1961).

At the time I was completing my endorsement on a float equipped Fairchild 82 with an experienced commercial pilot Hans vanderFlugt. On my first solo, after about four hours as co-pilot, I made a rookie mistake on glassy water that still makes me shake my head at having escaped with my life. The full story appears in the Flying Logbook Series: Fairchild 82: A Northern Workhorse.

2. Otter Down

In the present case, after the pilot configured the Otter for landing, he let it slowly descend towards the surface as he gently pulled back the yolk to bring his rate descent to about 150 fpm. By keeping his airspeed above stall (approximately 60 mph) with with full flaps, the aircraft was in a slightly nose high attitude. He made a textbook approach, but moments after the floats  touched the surface, the pilot caught site of large object breaking the surface directly in his landing path. He tried to apply full power to go around, but an instant later the craft was shaken by a violent impact that caused it to flip over on its back.

touched the surface, the pilot caught site of large object breaking the surface directly in his landing path. He tried to apply full power to go around, but an instant later the craft was shaken by a violent impact that caused it to flip over on its back.

Photo (Web Source): This is a view of the attitude of the Otter while sitting on the water. It is this attitude pilots seeks to achieve on a glassy water landing approach.

The pilot, instructor and three passengers were slammed violently forward, restrained only by safety belts. Lose objects also came flying forward, then fell to the ceiling as the craft came to rest in an inverted position. The wings were now resting on the water and within seconds the craft slowly began to sink, nose first, due to the weight of the 650 hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial engine.

While the pilot and instructor knew the craft would not sink further than the floats (if they had remained attached), they also knew time was of essence if they were to exit the fuselage before it submerged. After dropping from their seats and inflating their lifejackets, the five men entered the water through various exits and were on the surface just in time to see the wings, then fuselage slip below the surface. After the craft was fully submerged, it came to a rest as the giant air filled EDO floats settled in the water. Less than five minutes after the aircraft flipped, the five men were sitting on the floats waiting for rescue.

3. Cause of the Crash

So began another episode in the long history of the Big Kinosoo, that giant fish that lurks beneath the frigid, clear waters of Cold Lake. Beyond taking tons of fishing gear and more than a few boats over the years, this would the first suspected case of the giant fish taking down an aircraft. That it was an RCAF aircraft was of special concern. Had it been a civilian craft, the investigation might have ended differently, but as it belonged to the Air Force, the whole matter was soon cloaked in secrecy. Not only was it embarrassing to the RCAF to have it suggested on of their aircraft might have been taken down by a fish, it was perhaps more to the point about keeping things quiet about nature of these frequent flights around Northern Alberta and Saskatchewan.

While it was generally accepted there was considerable regular work for the Otters, many understood the “secondary” purpose was in transporting air force personnel on junkets to various hunting and fishing hot spots in the far north. Local fishermen and hunters  often spotted the planes “parked” on the remote waters at various trophy lakes and near moose hunting grounds.

often spotted the planes “parked” on the remote waters at various trophy lakes and near moose hunting grounds.

Photo (Web Source): An RCAF DHC-3 Otter on take-off run at Cold Lake. This aircraft followed on the heals of other venerable bush like the Noorduyn Norsman and Beaver.

Seibert, Touchwood, Winifred, Grist, Heart and dozens of others as far north as Fort MacMurray, promised a rewarding week-end for Air Force personnel and their friends. Civilians would gladly pay private operators thousands of dollars to board one of these junkets.

While the focus was on fishing and hunting, that elusive fish, The Big Kinosoo, was never far from their minds. The reason for searching lakes other than Cold Lake, is that many believed a number of giant aquifers, some the size of rivers, connected the northern lakes and it was through these aquifers fish could migrate between lakes. Alberta Fish and Wildlife officers, including our very own Johnny Donanco, remained skeptical, but over the years the number of tagged fish traveling from Cold Lake as far west as LacLaBiche and as far northeast as Peter Pond, confirmed this was happening on a regular basis.. However, most of the big fish from Cold Lake avoided Saskatchewan like the plague, as the waters in those lakes was too shallow, warm and weedy for the Cold Lake giants.

4. Rescue

At the crash scene, the weather was clear and calm as the men clung to the floats. The pilot told them what had happened and warned them to keep a wary eye out for a possible return of what he was now firmly convinced was a giant fish having taken down his craft. That a collision of some magnitude occurred was clear by he heavy damage to the front of the floats.

It was not long before rescue arrived as several late evening fishermen from Cold Lake had spotted the craft flip over. However, all of them were to far away to see what had caused the accident. My High School buddy, Guy Venne, was among those who headed to the scene. Guy was particularly attentive as he was an active member of the Cold Lake Volunteer Fire Department. He knew full well that if men were trapped inside the airplane time was of essence if they were to be saved.

On his way to the scene he snapped several photos, but by the time he arrived other fishermen had already plucked the men from the floats and were taking them to the Cold Lake Hospital and to notify the Air Force of the crash. Guy and a few others hung around the scene waiting for the Air Force units to arrive.

It was after dark by the time the Air Force crews secured the scene and by the next morning they had created an exclusion zone within the entire Bay. Military crash investigators who first arrived noted that Guy was taking pictures and told him the area was being cordoned off and that he would have to surrender his film. With access now blocked, Guy was among the last to have a good look the inverted aircraft and there was no doubt about what he observed.

It was after dark by the time the Air Force crews secured the scene and by the next morning they had created an exclusion zone within the entire Bay. Military crash investigators who first arrived noted that Guy was taking pictures and told him the area was being cordoned off and that he would have to surrender his film. With access now blocked, Guy was among the last to have a good look the inverted aircraft and there was no doubt about what he observed.

It would take three days before the aircraft was towed to a point near the main dock in Cold Lake where it could again be viewed by the locals. Just before crash surrounded the craft with screens, locals with binoculars noted divers bringing up quantities of fishing gear, rifles and camping equipment from the downed craft. After the aircraft was towed to the main dock in Cold Lake to be raised and removed to the base, it was now flipped right side up and the floats were no longer visible.

Gossip about the cause of the crash was circulating like wildfire and the fisherman who rescued the crew reported the pilot blaming a giant fish as having caused the accident. He had pointed to the heavy damage to the front of the floats as proof a collision had most certainly occurred.

5. The Investigation

After conducting a preliminary investigation at the scene, the plane was removed from the water. When it was lifted out it was clear the divers have completely enclosed the water filled floats with a canvas cover. Whether or not their was damage to the floats was kept from public scrutiny.

After removing the wings, the aircraft was transported to the Cold Lake Airbase and secured in Hangar #7. It was now ‘off limits’ to everyone except the investigative team.

investigative team.

Photo (Web Source): An Otter takes off from the Cold Lake base with the retractable gear extended. The front wheels (tip of floats) were used only to give longitudinal stability. When extended they were readily visible. After take-off from land, the pilot would normally retract the gear until it was again needed.

Rumours now began to circulate about the amount fishing and hunting gear removed from the aircraft. Some even speculated a moose carcass had been removed.

Some weeks later a hastily convened Board of Inquiry ruled the cause of the accident was “pilot error” stating the pilot, while on a ‘training flight’, failed to retract his wheels before attempting a water landing. The press release also stated the pilot was completing his float endorsement on the Otter at the time so it was written off as a rookie accident. This, however, did not stop the rumours.

Witnesses clearly remembered the aircraft having made two landings in French Bay before the crash. There is no reasonable explanation as to why the pilot, and an experienced instructor would have extended the gear for that third landing on water. Of course, stranger things have happened, but it seems highly unlikely. Further, none of the crash scene witnesses could recall seeing the gear extended and there was no possibility they would have been retracted by the pilot after the crash. Guy Venne, an fully trained emergency responder was particularly adamant on this point.

There was also the photographic evidence as captured by Guy. All efforts to have the film returned or released to the press were rebuffed by the Air Force. It appeared to everyone the Board of Inquiry was determined to sweep the entire incident under the carpet and that included posting the pilot of the ill-fated flight to the DEW Line as a radar operator. No one is certain what became of the Pilot Instructor. Neither man was ever made available for comment.

Many, including several military personnel, thought release of crash scene photos would have definitively established whether or not the landing gear was extended. The photos taken by Guy were classified as “Secret” and were likely destroyed.

6. A Similar Crash in British Columbia

By way of background, an RCMP Turbo Beaver (a modified precursor to the Otter) flipped over in a remote area of BC while attempting to land on Level Lake (70 km west of Dease Lake) in circumstances very similar to the incident on Cold Lake.

By way of background, an RCMP Turbo Beaver (a modified precursor to the Otter) flipped over in a remote area of BC while attempting to land on Level Lake (70 km west of Dease Lake) in circumstances very similar to the incident on Cold Lake.

Photo (by our next door neighbour, Bill Crawford) In this photo the Beaver settled to the bottom in shallow water before the floats reached the water. As can be noted, there is no damage to the front of the floats. This supports statements made by Guy and others that the wheels being extended would have been very visible. Also, in this crash, there was no damage to the front of the floats.

The Level Lake crash, which happened on Saturday, September 13, 2008, was observed by several hunters including our next door neighbour. Bill watched the crash and snapped the several photos immediately after the craft settled in the water. The men on shore rendered immediate assistance to those in the aircraft. The cause of the crash was clearly a simple mistake that cost the RCMP a completely refurbished Turbo Beaver.

In another similarity to the Cold Lake accident, the hunters at the scene later watched as other RCMP members who arrived at the scene, remove a quantity of fishing and hunting gear from the downed Beaver.

Many of these hunters were well aware this Beaver and other similar RCMP craft were often used for week-ends jaunts by senior members of the Force. As with the Air Force, the craft served a useful enforcement purpose, but it was altogether to tempting to let them just sit on the week-end when their were lakes and hunting grounds to explore.

For that reason alone it was not hard to convince the brass to have that Beaver completely restored and assigned full time to the Prince George Detachment. As in the Cold Lake RCAF Press Release, the RCMP in a press release referred to the ill-fated flight of that Beaver to Level Lake as being an “joint RCMP – BC Conservation enforcement project”. Needless to say most locals had a good laugh at that explanation as evidenced by the many blog posts that came out after the crash (Crash Report Link) and (Turbo Beaver Crash)

As for the Big Kinosoo in Cold Lake, he continues to make his presence known to this very day as will be outlined in the next two posts of this six part series.

Harold McNeill

Cold Lake, 2009

Link to Next Post: Sampi gets hooked

Link to Last Post: The Rush is on.

Link Back to Adventures Index

Diagram (Web Source) In glassy water landings, if the pilot fares out to early (to high), the aircraft can stall and nose into the water. To late means flying straight into the surface. In either case, the resulting crash will likely take the lives of all on board.

Diagram (Web Source). The proper procedure for a ‘glassy water’ landing is shown above

Photo (By Guy Venne) The Otter is slowly being lifted from the water using makeshift cranes (next photo). As can be noted in both photos, there is very little external damage evident on the main parts of the aircraft. When the aircraft was raised, divers had covered the floats in canvas.

Photo (Guy Venne). Workers continue to pump out the aircraft and prepare to lift it onto a waiting flat deck parked on the main dock. The wings were moved for transport back to the base. Homes along the Cold Lake waterfront north of the man dock can be seen in the background.

(2927)

Trackback from your site.

Comments (1)

very interesting story.It never amazes me over the years how the powers to be always decide what happened and no credence is given to the people that were there.