A Predictable Accident?

Above: Queen of the North en route through the Inside Passage on the West Coast of Canada. Having traveled on dozens of Cruise ships of various size, as well as hundreds of trips on BC Ferries including an occasional trip on the Queen of the North through the inside passage, I am amazed there are not more accidents given the oceans of the world can produce extremely challenging situations. The loss of that classic ship, the Queen of the North is just one more example of how things can go catastrophically within the blink of an eye.

Note: It appears that on occasion when making a simple one-word change, a whole paragraph can be replicated. I have not yet determined why this takes place, so please bear with me when this happens. Harold

Of the special items on the Queen of the North were several large murals that decorated the walls along the passageways. Photos, depicting various historical sites along the route, were accompanied by a written history of each site and surrounding area. The murals and stories were prepared under the direction of a long-time friend and former BC Provincial Archeologist, Bjorn Simonson. My wife, Lynn McNeill assisted in the preparation. As this work was completed perhaps a decade before the sinking, I don’t know if they were still being displayed when the Queen of the North sank on that fateful day in 2006.

(Activity: May 1, 2017 – 2712)

Follow-up News Reports, June 2013

Karl Lilgert, the navigating officer on the ill-fated Queen of the North, leaves the court after being found guilty of Criminal Negligence Causing Death. His being sentenced to four years in a Federal Penitentiary very much surprised me (see comments near the end of this post relating to the essential elements of a Criminal Negligence charge). I have no doubt the constant stream of inflammatory media reports as well as the vicious presentation by the Crown, had a strong influence on the jury.

to four years in a Federal Penitentiary very much surprised me (see comments near the end of this post relating to the essential elements of a Criminal Negligence charge). I have no doubt the constant stream of inflammatory media reports as well as the vicious presentation by the Crown, had a strong influence on the jury.

During my thirty-year police career, experience taught me that convicting someone on a charge of Criminal Negligence Causing Death was a particularly onerous task. As discussed further on in this article, each element of that particular statute presents a very real challenge for the investigators and crown.

In particular, I have been involved in other cases where the “wanton and reckless” disregard for life was considerably more egregious than in the Lilgert case, yet his case ended with a conviction. In my opinion, it was a stretch to have found each of the elements of the charge were proven in his case. I would be very surprised if either the charge or the sentence, perhaps both, were not tossed out on appeal.

Harold

March 22, 2010

Summary of Event

Today marks the 4th Anniversary of the sinking of the Coastal Ferry Queen of the North, a major British Columbia marine accident in which it seems fairly certain two people lost their lives. Tragic as those deaths were, it could have been much worse had it not been for the exemplary action of the Captain and Crew of the Queen of the North who were ably assisted by a number of civilian vessels from Hartley Bay and the crew of the Canadian Coast Guard Ice Breaker, Sir Wilfred Laurier.

Three days ago the Fourth Officer (Navigation Officer) from the Queen, who was on the bridge when the accident occurred, was charged with Criminal Negligence Causing Death. This follows considerable speculation over the past four years regarding the cause of the accident. In the midst of this speculation, there have been calls for a public inquiry as neither the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) nor a BC Ferries investigations was able to establish the definitive chain of events that lead to the Queen crashing into Gil Island. As is usual in these cases, fingers point toward human failure as the primary cause and as often happens in such cases, the press glosses over other possible contributing factors in favour of the most inflammatory. In this case, it was speculation about a possible spat (or an intimate liaison) depending on which press story you might choose to read.

Whatever may have been the cause many studies suggest this sort of accident is a “normal” event that while “predictable” it would be impossible to know when and where it might happen. Perrow (1) identifies three conditions that make a system likely to be susceptible to Normal Accidents. These are:

- The system is complex

- The system is tightly coupled

- The system has catastrophic potential

The Queen of the North exhibited all three items in spades. More often than not, it is just one of those systems, the human part, to which investigators, news reporters, owners (B.C. Ferries in this case) and others point, as being the key element that lead to the accident. How often have you read of a major airline accident that very quickly implied ‘pilot error’ was the causative factor. The same could be said for marine accidents or any other catastrophic event in which loss of life occurs. Is it possible to prevent such accidents?

Theory suggests the answer is “no”. The reason is actually simple as within any complex operating system accidents will happen no matter how finely tuned. The more complex the system, the more likely it will experience a catastrophic event (e.g Three Mile Island). While the Queen of the North was an old ship (by BC Ferry Standards), it was regularly updated with state of the art equipment. However, it is that updated to which may have inexorably lead to the sinking.

While the safety record of the BC Ferries (as compared to other ferry systems around the world) is exemplary, there are clearly flaws within their systems, such as that which seems to have lead to the sinking of the ship and the likely death of the two people believed to be aboard the ship. This story provides a bit of background on the sinking of the Queen as well as further information on the theory of why such accidents are destined to happen again.

The Sinking of a Queen

On March 22, 2006, the night watch had been on the bridge for less than two hours as the Queen steamed south through Granville Channel toward a midnight date with destiny at Gil Island. The Queen was headed to Port Hardy having departed Prince Rupert earlier in the  evening. Winds were gusting to 70 km/h in a passing squall. These conditions would not normally cause a problem for the 8,800 ton, 700 passenger Coastal Ferry as it traveling south along one of the more treacherous stretches of coastal British Columbia, the Inside Passage.

evening. Winds were gusting to 70 km/h in a passing squall. These conditions would not normally cause a problem for the 8,800 ton, 700 passenger Coastal Ferry as it traveling south along one of the more treacherous stretches of coastal British Columbia, the Inside Passage.

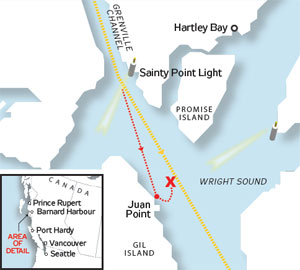

The Captain had retired to his cabin and the Second Officer went to the galley to grab a coffee. Two crew members remained on the bridge – the Navigation Officer (Karl Lilgert) and Helmswoman (Karen Briker). At this particular point, the two crew members were responsible for navigating the ship down the narrow, winding Inside Passage, a passage which required a number of small course corrections. Having made this trip many times, the crew was aware that in order to avoid a collision with Gil Island, a small course change to the port (left) would be required upon passing the Sainty Point Light House on entering Wright Sound.

Just before 00:20 hours, a startled Navigation Officer hollered for the Helmswoman to make a bold course correction (109 degrees) to Port. The Officer could just discern the outline of Gil Island looming out of the darkness. At this point, the ship was only 750 meters off course but in this narrow channel, was in imminent danger of colliding with the north-east shore of the Island. Several reasons were posited as to why the course correction was not immediately made as the ship passed Sainty Point.

It is reported the Helmswoman failed to respond to the order to disengage the autopilot and even though there were several plusible explanations as to why she didn’t, the one the stuck was the suggestion of a liason taking place between her and the first mate while on duty on the bridge. Even though this suggestion was mere speculation, it flowed to the top as the most likely cause, that being human error. Even if she had responded within a few seconds, it was considered unlikely that the Queen would have been able to avoid the collision. Other possible causes seem to have been given short shrift.

So it was, at 00:41 hours, at full night-cruising speed, the ship was rocked by a thunderous roar and the torturous sounds of shearing steel. The ship healed over to the starboard throwing the crew to the deck. Passengers were tossed from their bunks or thrown against bulkheads. For the next several minutes, the ship was engulfed in chaos. As the ship slid off the reef, it settled back and began taking on massive amounts of water through a gigantic hole in the steel hull. The car deck and engine room began to flood. Several crew members below deck working or in their quarters, barely managed to escape the inflow of water.

The Captain immediately joined the crew on the bridge. As damage reports came in, it did not take more than a few minutes to come to the full realization that the ship had been mortally wounded and would sink. The Captain ordered the crew to abandon ship and sounded the alarm to alert the passengers, most of whom were in their staterooms for the night. The well-trained crew acted quickly. A final check conducted at 01:30 hours indicated all passengers and all but a handful had been evacuated.

A final check conducted at 01:30 hours indicated all passengers and the crew were accounted for, with only the Captain and those on the ship left to enter a a lifeboat. Although evacuation of the ship was orderly in an extremely difficult situation, it was not possible in the time allowed to conduct a name check of all passengers who had been transferred to various lifeboats. Following the final report, the Captain ordered the remainder of the crew to abandon ship. The Captain and First Officer were to be the last to leave. As their lifeboat pulled away, they quietly watched as the Queen slipped slowly beneath the surface to join the hundreds of ships which had suffered a similar fate along the BC Coast over the past three centuries.

Although safely off the ship, everyone was still in considerable danger as the wind, light rain and cold made for brutal conditions. If a life boat should happen to sink in this desolate area, the lives of those on board would, in just a few minutes, be in grave danger due to the frigid water. Even in the lifeboats, it was necessary to fight off hypothermia as many passengers were only dressed lightly having been in night attire and sound asleep when the collision occurred. Fortunately, help was at the scene in short order when a number of boats from the nearby fishing community of Hartley Bay arrived in response to the SOS. They began transferring passengers and crew back to the village.

The Canadian Coast Guard Arrives

After the initial SOS, two Canadian Coast Guard Cormorant helicopters and a 442 Squadron Buffalo Aircraft from Comox were dispatched to the scene. By sheer luck, the Canadian Coast Guard Icebreaker, Sir Wilfred Laurier, had been heading into Barnard Harbour, about 25 km south and would not take long to arrive at the scene. On hearing the SOS it had already dispatched a high-speed Rescue Craft, The Laurier I, which would arrive by 02:00 hours.

On arrival and in deteriorating weather, the three aircraft and the Sir Wilfred Laurier remained on station to insure all passengers and crew were safely transferred to Hartley Bay. In the middle of a stormy night, this was a remarkably well-coordinated rescue effort involving dozens of civilian and government craft.

Hartley Bay was a beehive of activity as passengers and crew were provided with drinks, food, clothing and shelter in private homes and community buildings. Every resident came out to help. The ship’s Captain then ordered a passenger count and it was determined sometime later that two passengers appeared to be missing. Initially, it was suggested they may have left the area; however, when they could not be located after two days, it was presumed they went down with the ship.

The exact chain of events that led to this tragic accident has never been determined with any degree of certainty. While it appears clear the crew on the bridge held final responsibility for making a course change on approaching Gil Island, on the advice of their lawyers, no one, other than the Captain, would provide an account of their actions pending the result of an ongoing criminal investigation. It was also reported BC Ferries would not give any assurances that any statements made by the crew could be given “without prejudice”.

As a result, speculation ran rampant. Was the crew on the bridge remiss in their duties? Was training inadequate or was the equipment faulty? Why did the ship go off course without an alarm sounding? Had the BC Ferries management team failed in some other manner? The item to which investigators, and eventually the crown most often foccussed, was the relationship between the Navigation Officer and the Helmswoman. In the criminal charge this possible (yet never proven element) distraction was held out as the cause of the accident. In the absence of an accounting of their actions, the three crew members, including the officer on a break, were terminated. As is frequently the case in major accidents of this sort, human error was held out as the most likely cause.

For their part, B.C. Ferries was more than willing to sacrifice a few long term employees in order to deflect any criticism of other shortcomings within the system (technical and administrative), shortcomings to which the Captain of the ship had pointed. He to was fired even though his actions and that of his crew during the evacuation were held out as being of the highest order.

A Normal Accident

It might seem surprising, but the sinking of the Queen, while unquestionably tragic, was an inherently predictable, normal accident. Not predictable in the sense that anyone could possibly have known the Queen would sink on that particular night and not normal because it happens every day, but predictable in the sense that in any highly technical system such accidents will periodically occur. We see that happen almost every week somewhere in the world where an aircraft goes down or a ship sinks.

It is now well established that the great majority of these accidents are caused not by a single, catastrophic event or a single error on the part of a human component, but by a series of smaller events. A theory on this very subject was proposed by Yale sociologist Charles Perrow. It is called the “Normal Accident Theory”.

According to the theory, in any complex system, the interconnection of hundreds of sub-systems, including human resources, makes it impossible to plan for every contingency. Even at that, the failure of any one part or even several parts of the system seldom leads to a major accident. Every so often, however, these failures can combine in a certain unpredictable sequence such that an accident will result. In this sense, the accident is a ‘normal’ part of the risk of operating a highly complex system.

The job of accident investigators is to piece together the chain of events that led to the accident and, if possible to suggest changes in operating systems that might prevent future similar accidents. What accident investigators and system planners cannot do is predict the next sequence of ‘random’ events that will lead to the next accident. However, one must not forget that the chance of a future accident happening in exactly the same manner as a past accident is astronomically high.

In the case of the sinking of the Queen of the North, one can be reasonably certain that any error in judgment which may have occurred on the bridge that fateful night was only one part of a series of systemic failures (technical and human) that ultimately led to the accident. The Navigation Officer and the Helmswoman appear to have been part if that sequence of events that lead to the sinking of the Queen. While they may have played only a small part in the overall failure, fingers will most certainly be pointed in their direction as finding human error always seems tantamount in the investigation of major incidents such as the sinking of the Queen of the North.

Criminal Charges Laid

Over the years there have been a number of high profile public transportation accidents in circumstances roughly similar to those of the sinking of the Queen. What is unusual in this case is that a criminal charge has been laid against the Navigation Officer. Whether a momentary distraction (if that is what happened on the bridge of the Queen that fateful night) will be sufficient to support a conviction remains to be determined by the Courts. My experience in investigating a number of criminal events (where people were most certainly responsible in one form or another), suggests proving Criminal Negligence causing death as regards the sinking of the Queen, will be extremely difficult.

In a charge of Criminal Negligence Causing Death, three particular elements must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt:

1. There must have been a specific “act or omission” that led to the death;

2. There must have been “wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of others”, and;

3. This conduct must have caused the death.

Whether other considerations factored into the laying of this particular charge remains to be seen, but you can be sure the pressure will be on to secure a finding of guilt.

Why were two people missing on the ship?

A subject that has been little reported is why, out of 101 persons on board the Queen that fateful night, did only two fail to evacuate the ship? Were they trapped on the car deck? Having travelled on BC Ferries many hundreds of times, including a few trips on the Queen of the North, it is well understood that remaining on the car deck during transit presents a degree of danger if the ship should run into difficulty. While the chance of an accident is extremely remote, these accidents do happen as happened that night on the Queen.

As an example, in one accident that occurred in Active Pass (near Victoria) a Russian Freighter and a BC Ferry collided. Several cars on the ferry car deck, including one belonging to a friend, fell through a giant gash in the side of the ferry. If our friends had decided to nap in their car on that particular trip, they most certainly would have ended up spending an eternity at the bottom of the pass. I do not recall any charges being laid in that accident, although it seems likely a navigation mistake was made on one ship or the other.

In the case of the sinking of the Queen, the crew carefully checked every cabin and all other locations above water. All reasonable checks were made to ensure everyone had been evacuated before the Captain and the First Officer abandoned the ship. While it is a tragedy that one couple lost their lives, the question still remains – why did those two not evacuate the ship with everyone else?

It is doubtful this question will be answered in a criminal trial. As in most cases like this someone has to pay the price in order to protect the system (BC Ferries) from being held responsible for any systems failures. In this case it is the First Officer and the Captain.

Harold McNeill

Victoria, BC

March 22, 2010

Note: The author has no connection with BC Ferry system other than being a periodic user of the service.

(1) References:

Perrow, C. (1984/1999). Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies, Princeton University Press.

Various newspaper articles and internet postings on the sinking of the Queen of the North.

Photos from various locations on the Internet.

(3058)

Tags: Karen Briker, Sir Wilfred Laurier, Wright Sound, Queen of the North, Colin Henthorne, Karl Lilgert, Bjorn Simonsen, Lynn McNeill

Trackback from your site.