Posts Tagged ‘David McNeill’

Patricia Pearl Humphrey (1916 – 2013)

Patricia Pearl Humphrey (Schirrmacher/McNeill)

(1916 – 2013)

The youngest child of a family of

Canadian Pioneers

On Saturday morning, October 26th, 2013, our dear Aunt Pat passed away at her home in Stony Plain, Alberta. At age 97, Aunt Pat was the last of eleven siblings of a family that pioneered in South Dakota in the 1800s and then Saskatchewan at the beginning of the last century.

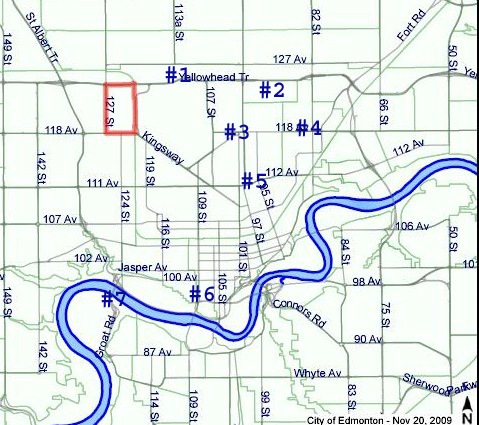

Her parents, James Wallace McNeill (1866-1938) and Martha Ellen McNeill (Church) (1874 – 1958) married in 1893 in Chamberlain, South Dakota, then, 17 years later, after facing an ongoing drought and constant unrest in the Dakotas, pulled up stakes and headed to Canada. After entering through Peace Portal in Manitoba, the woman, including Martha’s mother (her husband had passed away), and the youngest children caught a train west while the father and older boys, Clifford and James, drove the wagons and cattle. They all landed in North Battleford, Saskatchewan in the spring 1910.

On departing from South Dakota, the couple had seven children in tow – Dave (2, my father), Elizabeth (5), Hazel (8), Irene (9), Ruby (12), Clifford (14) and James (16), not a move many of us would ever consider tackling . Not only that, in the fall of 1910, after arriving in North Battleford, the twins, Armina and Almira, joined the family.

After checking out the lay of the land, James and Martha selected a homestead in Birch Lake, about 60 miles north. It was there the final two children, Floyd and Patricia Pearl, were born. The family worked the land until the father, James, passed away in 1938. A few years after his death, perhaps the mid 1940s, Martha moved back to North Battleford where she remained until her passing in 1958.

(2040)

The McNeill Family: Edmonton

Photo (From Web): The stately H.A. Gray Elementary School in Edmonton where Mom registered Louise and I in late August, 1949. It was a far cry from our one room school in Harlan, SK (see Chapter 2). Also, reference footer photo for comparison to a similar building in Victoria.

Link to Next Post: Pibroch

Link to Last Post: Dad is Missing (Last of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

Link to the Old School House (First in the Harlan Series)

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

Chapter 1: The Gypsy Years

When Dad and Mom (Dave and Laura McNeill) took Louise and me 1 to live with Aunt Liz and Uncle Warren, in Harlan, Saskatchewan early in the spring of 1949, it was the first time we were separated from our parents. While we had made many moves in our short lives, this was just the beginning of being away from them for various periods of time ranging from a few months, to nearly a year. Our lives became a whirlwind of short-term home stays, new schools and new friends, many of whom remained steadfast for the rest of our lives.

Even our old pal Shep, the amazing Collie Cross, was left far behind in the care of our good friend Mr. Goodrich, our trapper neighbour at Marie Lake (A Final Farewell). Although the loneliness of being separated from Mom, Dad, Shep and our wilderness way of life, left a gapping hole in our lives, we had every reason to believe the hole would be filled once we settled in Edmonton.

Well, things did not turn out as planned and, in fact, Edmonton would bring the near death of our Mom and her younger sister, Aunt Marcia and the death of our one our best friends.

1Aunt Liz’s first husband Tart, a rodeo bronco rider, had passed away a few years earlier and Aunt Liz, Dad’s sister, had married Dad’s friend Warren Harwood around the time we were all living north of Cold Lake. (Smith Place)

(2676)

Harlan: A Tragic History – Chapter 2 of 6

Photo (Frog Lake Memorial): One man who died was the John Delany, the Grandfather of my Aunt Hazel (wife of my mom’s brother Melvin Wheeler), all part of the interesting history of our family. Note, many of these historic signs still denote the event as a Massacre in the midst of the Northwest Rebellion. Little mention is made at these historic sites of the attempt by an “Indian Agent” follow the “letter” of the laws passed in Ottawa, to starve the local bands into full submission to his wishes.

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

THIS STORY IS CURRENTLY BEING PROOFED AND UPDATED

Early Spring, 1949

While our home in Marie Lake, Alberta (20 miles north of Cold Lake), was nestled within the pristine beauty of the lakes and evergreen forests dotting Northwestern Alberta, Harlan District was spread out along fields and poplar forests that gently rose from the banks of the North Saskatchewan River. Situated just inside the Saskatchewan border with Alberta, the community was less than ninety miles south-southeast of Cold Lake. Today, it remains a small farming community. Most things remained the same when my sister, Louise, and I lived there for a few months over the spring and summer of 1949. Louise was six and I was nine when we moved in with Aunt Liz (Dewan-McNeill) and Uncle Warren Harwood lived on a farm property in an area that was home to many in the

extended Harwood Family.

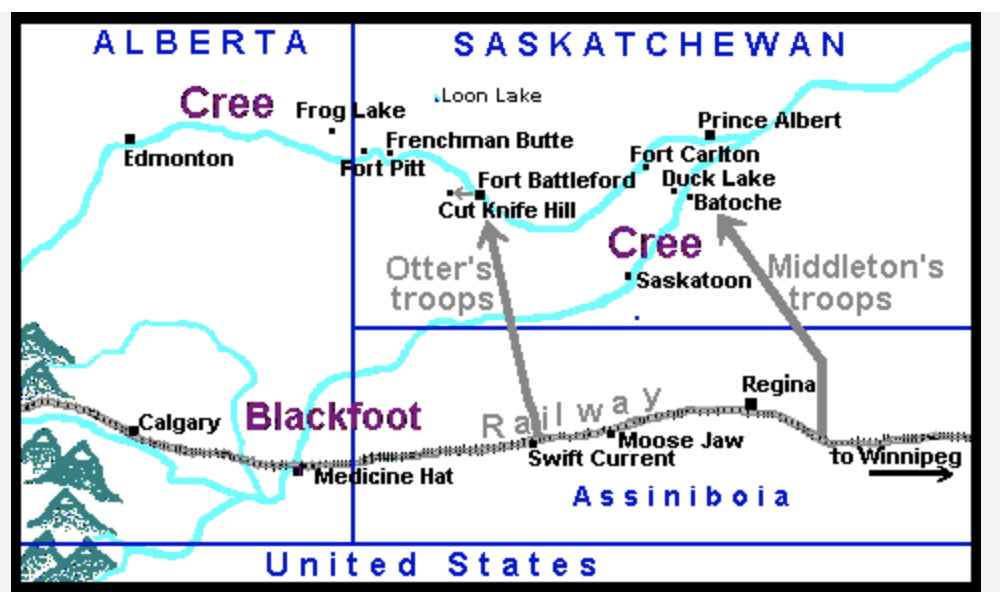

During that spring and summer, our cousins Betty (10) and Stanley (7), explored the grassy fields and poplar woodlands around the farm. Of course, we were oblivious to a significant piece of Canadian History that played out just over sixty years earlier – The “Frog Lake Massacre of 1887”.

During that spring and summer, our cousins Betty (10) and Stanley (7), explored the grassy fields and poplar woodlands around the farm. Of course, we were oblivious to a significant piece of Canadian History that played out just over sixty years earlier – The “Frog Lake Massacre of 1887”.

Calling it a massacre was wrong, as the more appropriate name should have been “Attempted Genocide at Frog Lake” or “The Frog Lake Uprising“. While some changes slowly seeped into the historic narrative, much in the way of naming is yet to be addressed by the Federal and Provincial Governments in the naming of sights and events.

That ill-fated attempt at genocide might have succeeded if bands had not risen against the deliberate starvation through federal government policies designed to subjugate the original inhabitants of that area. While the Indian Agent in Frog Lake bore a substantial part of the blame, Sir John A. MacDonald and his government were the architects of a policy that decimated many local Indian bands across Canada. Some tried to justify what happened as part and parcel of the challenges of “taming this new land”, but that explanation falls far short in explaining the brutality of the government policy and particularly the actions taken by many “Indian Agents.” assigned the task of handing out food supplies.

At the time the four of us were playing in the fields, we now know a member of our own family, Aunt Hazel Wheeler (nee Martineau), the wife of Mom’s brother, Melvin Wheeler, traced her family history directly to those tragic events that played in the Harlan District over the fall of 1887.

The farm where we lived with Uncle Warren and Aunt Liz Harwood (nee McNeill) was twenty-five miles southeast of Frog Lake, thirteen miles from Onion Lake and five miles west of Fort Pitt. The district became the epicentre of a rebellion of which the charismatic Métis leader, Louis Riel, was the prime mover, who chaffed at the injustices heaped upon the Cree and other tribes by the Federal Government. Riel was able to weld the diverse Indian Nations together in common purpose.

In his book, The Frog Lake “Massacre”, Bill Gallaher writes: “Superintendent Crozier and a contingent of policemen aided by a small volunteer force from Prince Albert, had confronted Louis Riel and his rebels, some of them Cree, at a place called Duck Lake, a few miles east of Fort Carlton. After the ensuing battle, 14 men lay dead.” (p. 102).

News of the confrontation quickly spread to the tribes in the Frog and Onion Lake area, where activist leaders, including Wandering Spirit, Man Who Speaks Another Tongue, and others who, gained a substantial following. Much of their anger was focused on one man, Thomas Quinn,

the Ottawa-appointed Indian Agent at Frog Lake. The man was an arrogant, stingy Scotsman responsible for enforcing Federal Government policy regarding the distribution of food supplies. The bands were in desperate straits after being forced out of their traditional hunting grounds and left utterly dependent upon government handouts.

Quinn took his directions to heart by forcing the largely peaceful Indian bands to bow to his every whim before he would release any food and other supplies agreed upon in the treaties. As the tribes became increasingly desperate and as their land base continued to shrink under the onslaught of the white settlers, it was not long before their traditional food supplies all but disappeared. Pleas for relief emanating from moderate leaders, including Chief Big Bear, fell upon deaf ears at Fort Battleford and Ottawa.

Having heard of Louis Riel’s initial successes in confronting government forces, activist leaders convinced many warriors to stand and fight rather than bow to the dictatorial Indian Agent. To resolve the situation, a meeting with the local settlers and Indian Agent would occur at Frog Lake:

“The air in the room was hot and close, thick with pipe smoke and body odour. All of the whites in Frog Lake had gathered in John and Theresa Delaney’s house to discuss Dicken’s message (a message from Inspector Dickens of the North West Mounted Police suggesting all the white settlers at Frog Lake, evacuate the community immediately and head to Fort Pitt), viewed by some as an emergency. It was near midnight as Theresa served tea and coffee strong enough to make sleep a far off in the country.” (Gallaher, p. 103)

“I noticed, as I’m sure others did, that he didn’t mention the Indian’s dislike of Quinn – they always called him “Dog Agent” or “The Bully” behind his back – and that perhaps he should go too.” (Gallaher, p. 105)

“Early the following morning, the group was taken hostage by the rebels, then under the leadership of Wandering Spirit. While being forced back to the Cree village, Quinn suddenly stopped and refused to follow instructions. Wandering Spirit stepped in front of the belligerent man, “You have a hard head, and I wonder if there is anything in it? He raised his rifle and shot Quinn through a head not so hard that a bullet couldn’t split it open…” (Gallaher, p. 106)

The sudden, violent killing of the “Dog Agent”, Quinn, left the remaining hostages scrambling for their lives:

“My mind was churning madly. We hadn’t taken more than a few steps when John Delany cried, “I’m shot!” He reeled several feet away like a drunkard, then staggered back and collapsed at Theresa’s feet. Oh, my God! Theresa cried. “Father, Father!” As she called, one of the priests, Father Fafard, came running to her side and dropped to his knees. Delany lived only long enough to hear the priest administer consolation and say, “You are safe with God, my brother.” These words had just passed Fafard’s lips when Man Who Speaks Another Tongue shot him in the face. He fell across Delany’s corpse.” (p. 128)

The uprising had passed the point of no return as the rebellious leaders and their followers headed toward Fort Pitt to confront the government forces. Only a few days passed before miserable weather a lack of weapons, food, and other supplies led to the collapse of the resistance, but not before many more had died in skirmishes in the valleys and hills surrounding Harlan, Fort Pitt and Frenchmans Bute.

The eight Indians, considered ring leaders, were arrested, and taken to Fort Battleford for trial, the outcome of which was never in doubt. After being convicted, they were hanged on makeshift gallows within the Fort. Chief Big Bear, the moderate leader of the Cree, who was present for the hangings, was then put on trial believing that he, as the leader, was ultimately responsible for the rebellion. After being convicted, he spoke eloquently in defence of his people:

Photo (Web File): The eight Rebellious leaders were hanged in a public event at Fort Battleford barrack square on November 27, 1885. Their bodies were unceremoniously interred in a scrubby bush area below the Fort. More photos and words follow near the end of this story. The men hanged—Kah-Paypamahchukways, Pahpah-Me-Kee-Sick, Manchoose, Kit-Ahwah-Ke-Ni, Nahpase, A-Pis-Chas-Koos, Itka, and Waywahnitch.

Following the hanging, Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) was put on trial a sad end to a popular leader. In 1871 he was the leading chief of the Prairie People and by 1874, headed a camp of 65 lodges (approximately 520 people). His influence rose steadily in the following years, reaching its height in the late 1870s and early 1980s. Due to events leading to the Frog Lake Uprising, his power was slowly eroded by the more aggressive leaders for reasons outlined later in this story. Following is the full Chief Big Bears full speech to the court as translated from the original Cree.

I think I should have something to say about the occurrences which brought me here in chains! I knew little of the killing at Frog Lake beyond hearing shots fired. When any wrong was brewing, I did my best to stop it in the beginning. The turbulent ones of the band got beyond my control and shed the blood of those I would have protected. I was away from Frog Lake a part of the winter, hunting and fishing, and the rebellion had commenced before I got back. When white men were few in the country, I gave them the hand of brotherhood. I am sorry so few are here who can witness for my friendly acts.

Can anyone stand out and say that I ordered the death of a priest or an agent? You think I encouraged my people to take part in the trouble. I did not. I advised them against it. I felt sorry when they killed those men at Frog Lake, but the truth is when news of the fight at Duck Lake reached us, my band ignored my authority and despised me because I did not side with the half-breeds. I did not so much as take a white man’s horse. I always believed that by being a friend of the white man, I and my people would be helped those of them who had wealth. I always thought it paid to do all the good I could. Now my heart is on the ground.

I look around me in this room and see it crowded with handsome faces—faces far handsomer than my own. I have ruled my country for a long time. Now I am in chains (Photo Left on right arm) and will be sent to prison, but I have no doubt the handsome faces I admire about me will be competent to govern the land. At present, I am as dead to my people. Many of my band are hiding in the woods, paralyzed with terror. Cannot this court send them a pardon? My own children—perhaps they are starting and outcast, too, afraid to appear in the big light of the day. If the government does not come to them with help before the winter sets in, my band will surely perish.

But I have too much confidence in the Great Grandmother to fear that starvation will be allowed to overtake my people. The time will come when the Indians of the North-West will be of much service to the Great Grandmother. I plead again to you, the chiefs of the white man’s laws, for pity and help to the outcasts of my band!

I have only a few words more to say. Sometimes in the past, I have spoken stiffly to the Indian agents, but when I did so, it was only to obtain my rights. The North-West belonged to me, but I perhaps will not live to see it again. I ask the court to publish my speech and to scatter it among the white people. It is my defence.

I am old and ugly, but I have tried to do good. Pity the children of my tribe! Pity the old and the helpless of my people! I speak with a single tongue, and because Big Bear has always been the friend of the white man, send out and pardon and give them help! How! Aquisanee—I have spoken!

Big Bear was sentenced to three years of hard labour to be served at the Stoney Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. He was taken away in shackles and leg irons and put on a train heading to Stoney Mountain – a proud leader to the end. He died 1888.

Eighty years later, the following passage, written by our Aunt Hazel Wheeler (Martiniau) about her parents and Grandparents, appears in “The Treasured Scales of the Kinosoo“, a book of life stories of those who settled the Cold Lake area:

“Father (referring to her father) was transferred to Onion Lake in 1901 as a Hudson’s Bay Company Agent. He met and married Margaret Delaney. Margaret was the daughter of a native mother and an Irish father. Her father (Aunt Hazel’s Grandfather), John Delany, was killed in the Frog Lake Massacre, and she was raised by nuns at Onion Lake. Father was part French and part Scottish, and he used to tell us that we were a little bit of everything and not much of anything.” (p. 4)

Aunt Hazel was one of thirteen children in the Martineau family. It was a grand family that included five adopted children saved from the orphanage after the death of their parents. It is little wonder that Aunt Hazel’s mother was known as ‘Grandma Martineau’ to everyone in the Cold Lake area. She was well into her eighties when she passed away (reference picture of Grandma Martineau sitting on the logs at the Martineau Camp in Chapter 3 of that series).

Photo (Family Files). Aunt Hazel and Uncle Melvin Wheeler are sitting with their two sons, Timmy, and Randy, at their home in Cold Lake.

The following quotes from Aunt Hazel are added as they relate to other events and people in those early years of our family travels throughout the Northwest.

“Johnny Cardinal operated the ferry on the North Saskatchewan River near Frog Lake at the time of the Massacre.” (p. 5). (The Cardinals were another well-known Cold Lake family).

“A group of surveyors worked north of Cold Lake before 1910, setting their base camp at an unnamed river that flowed into Cold Lake. They depended upon Adrian (Adrian Martineau, one of Aunt Hazel’s brothers) for their food supplies. On one occasion, the supply wagon bogged down due to heavy rains at Onion Lake. When the needed supplies finally arrived, the head surveyor announced that he named the river at their base camp Martineau to remind Adrian of when he and his men (the surveyors) almost starved.” (p. 5)

Adrian passed away in 1944, the year we moved to Cold Lake and lived on the banks of the Martineau River, very near the area where the surveyors almost starved in 1910. In the summer of 2010, our oldest son, Jay McNeill, and I visited many historic sites stretching from Frog Lake and Onion Lake to Fort Pitt and Fort Battleford. Our visit included a stop at the grave sites of the eight settlers killed and buried at Frog Lake and the eight Indian leaders hanged and then buried on a sidehill below Fort Battleford.

Given that Fort Battleford is a National Historic site, it is a national disgrace that the hanged men, leaders of the day who attempted to help their people, have been relegated to weed-infested, rocky sidehill several hundred feet below the Fort. They were heroes, and their History is cast aside in favour of a different narrative of those times.

below the Fort. They were heroes, and their History is cast aside in favour of a different narrative of those times.

The graves below Fort Battleford are located no more than a few hundred yards from the spot where first our Grandparents McNeill and several of their children, including our Dad (two years old at the time), camped in 1910 as they were making their way by wagon train from South Dakota to Alberta to build a new life on the shores of Birch Lake. Birch Lake is some seventy miles north of Fort Battleford near Glaslyn, where Chapter 1 of this story began.

One year later, in 1911, our future Great-Grandparents and Grandparents Wheeler and some of their children, immigrated from Michigan to Sibbald, Alberta. In 1924, due to serious drought conditionst, some of those same families (some now married and with children of their own), left Sibbald, Alberta. for Birch Lake, Saskatchewan. Included in that group was a child who would later become our mother, Laura Skarsen-McNeill (Wheeler). During that wagon-train trip, they made a five-day layover below Fort Battleford, before leaving for Birch Lake, where they would stake a land claim on quarter section of land very near the McNeill family.

The full story of both families travels from the United States to Canada in 1910, is now being written and will become the first half of a family book that follows our families for a hundred years from the 1860s – 1960s

Harold McNeill

July 2010

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

Link here to photo’s of Frog Lake adventure: LINK HERE

September 19, 2012. The following information was plucked from a Genealogy site:

Also, a note by Phylis Wicker Glicker

Hazel Martineau [Wheeler] daughter of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau b. Oct. 18, 1875, St. Boniface, Manitoba, Canada, and Margaret Delaney b. Nov. 30, 1885, Frog Lake, Alberta, Canada. Adrien is the son of Herman Martineau b. Brittany France mar. (1) Annie Macbeth (2) Angeline LaBelle. Herman Martineau is the son of Ovit Martineau b. Brittany, France. I have just begun researching the Delaneys and Martineau”s so I don’t have much. But I would love to hear from you and share what I have. I was married once to Frank Martineau, grandson of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau and would love to learn about Margaret Delaney’s family for mine and my children’s sake.

Email: pwicker@telus.net

Harold Comment: I am not sure if this is correct, but it seems to fit with the details I have previously researched.

(4164)

Marie Lake: Explosion – Chapter 3 of 11

Photo (Web). A wood cookstove that nearly ended our mothers life.

Link to Next Post: Link to Easy Come, Easy Go

Link to Last Post: Link to Growing Up in the Wilderness

Link to Family Stories Index

July, 1947

It was one of those quiet, lazy July mornings at Marie Lake. The dead calm waters reflected the morning sun and the leaves on the poplar trees, usually twisting and fluttering in the slightest breeze, hung as if frozen in time. The only noise to be heard was the quiet chatter of a few birds and of the laughter of Louise and me as we  dredged out wet sand to complete our giant sand castle – to be a surprise for mom and dad.

dredged out wet sand to complete our giant sand castle – to be a surprise for mom and dad.

Suddenly, the serenity of the morning was bluntly ended by a loud, deep ‘whooomp’ coming from the direction of the house. A split second later the silence was further pierced by a blood curdling scream that echoed through the trees and down to the water. Louise and I sat there, momentarily frozen.

With the screams rising in intensity, we jumped up and run towards the house. As we topped the small sand bank we saw mom running with flames and smoke rising from her body. We were stricken with fear at a site we couldn’t fully comprehend.

After a short distance, she fell and rolled in the sand, grass and pine needles covering the yard. We stopped dead in our tracks not knowing what to do. At that moment dad came running from the mink pens. He frantically tried to smother the flames with his jacket but it wasn’t large enough to cover her whole body. Each time he moved the jacket, flames would spring to life. An eternity passed before the flames were finally extinguished. The nauseating smell of burnt cloth, plastic and flesh permeated the air.

Dad hollered: “Harold, Louise, get a sheet off the bed.”

(1763)

Marie Lake: The Mink Pen Adventure – Chapter 1 of 11

A line squall moves toward our boat as we crossed Marie Lake. The high winds and waves placed us in mortal danger.

Link to Next Post: Link to Growing Up in the Wilderness

Link to Last Post: Link to Near Death on the Dock (End of Part II)

Link to Family Stories Index

1947 -1949

Marie Lake was suddenly rough, very rough, as the wind stirred up white frothy waves to a height of three or four feet. The ice had been out for no more than a week and small chunks could still be seen floating nearby. We were being drenched by the freezing spray and at this moment were in imminent danger of being thrown into the freezing cold, dark waters.

Aunt Marcia1 reflected upon that hair raising boat trip:

“That crazy uncle of mine was so smart but he had no sense when it came to being cautious. When we left the dock he could see storm clouds on the horizon and the wind was rising. I was only fifteen but even I knew Marie Lake could quickly become rough enough to swamp our small boat.

Now, here we were, spread-eagled on top of a boat covered with stupid mink pens. Mink pens, can you believe it – stinking, dirty mink pens. I suppose we were lucky Uncle Dave had not kept the mink in them. I asked him to wait, but he laughingly chided me – come along or stay by myself. Stupid me, I went along. Now we were in the middle of the lake and things were going from bad to worse.”

(1669)